California has been at it again, proving to everyone in the country that the state most loudly proclaiming to be the leader against CO2, the disproven boogeyman of “Climate Change,” is really not interested in the environment at all, but the element of control Climate Change policies provide. There really isn’t any other explanation for what is happening in the Antelope Valley where local government has been taking individuals who live off the grid in the middle of nowhere off of their land by force of law.

In a video shot by Reason TV, several stories are told by the residents of Antelope Valley, most of them living in unique style homes built by their own hands, others living off the electric and water grids doing nothing but living their lives and minding their own business. Many of these residents have received a knock on their doors only to find armed men with guns drawn over municipal and county codes.

That’s right, a virtual armed raid over codes that most people, if viewed objectively, would find onerous and ridiculous to begin with. Nevertheless, residents have found themselves charged with numerous misdemeanors, excessive fines, extortion, and jail over “code enforcement” that is allegedly designed to “protect the public.” These people are then forced off their land in an area that has admitted “homeless problem.”

The issue in Antelope Valley is not new. In fact, it goes all the way back to 2011 when Mars Melincoff wrote an article about the situation for LA Weekly entitled, “LA County’s Private Property War,” where she wrote,

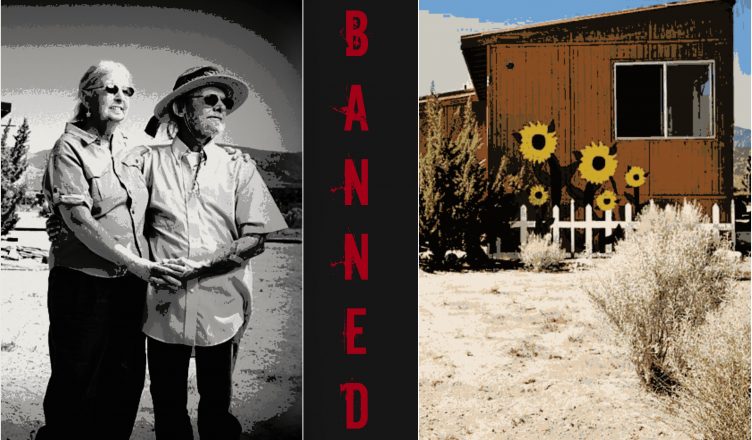

In Llano, in the middle of the Southern California high desert, a bewhiskered Jacques Dupuis stands in front of what was once his home. His laid-back second wife, Marcelle, her long, silver hair blowing in the breeze, takes a drag on her Marlboro Red as they walk inside and, in thick French Canadian accents, recount the day in 2007 when the government came calling. “That’s the seat I have to offer you,” she tells a visitor, motioning to the exposed, dusty wooden floor planks in what was once a cozy cabin where Jacques spent much of his life, raising his daughter with his first wife.

On Oct. 17, 2007, Marcelle opened the door to a loud knock. Her heart jumped when she found a man backed by two armed county agents in bulletproof vests. She was alone in the cabin, a dot in the vast open space of the Antelope Valley, without a neighbor for more than half a mile. She feared that something had happened to her daughter, who was visiting from Montreal.

The men demanded her driver’s license, telling her, “This building is not permitted — everything must go.” Normally sassy, Marcelle handed over her ID — even her green card, just in case. Stepping out, she realized that her 1,000-square-foot cabin was surrounded by men with drawn guns. “You have no right to be here,” one informed her. Baffled and shaking with fear, she called her daughter — please come right away.

As her ordeal wore on, she heard one agent, looking inside their comfortable cabin, say to another: “This one’s a real shame — this is a real nice one.”

A “shame” because the authorities eventually would enact some of the most powerful rules imaginable against rural residents: the order to bring the home up to current codes or dismantle the 26-year-old cabin, leaving only bare ground.

“They wouldn’t let me grandfather in the water tank,” Jacques Dupuis says. “It is so heart-wrenching because there was a way to salvage this, but they wouldn’t work with me. It was, ‘Tear it down. Period.’ ”

In order to clear the title on their land, the Dupuises are spending what would have been peaceful retirement days dismantling every board and nail of their home — by hand — because they can’t afford to hire a crew.

Tough code enforcement has been ramped up in these unincorporated areas of L.A. County, leaving the iconoclasts who chose to live in distant sectors of the Antelope Valley frightened, confused and livid. They point the finger at the Board of Supervisors’ Nuisance Abatement Teams, known as NAT, instituted in 2006 by Los Angeles County Supervisor Michael Antonovich in his sprawling Fifth District. The teams’ mission: “to abate the more difficult code violations and public nuisance conditions on private property.”

L.A. Weekly found in a six-week investigation that county inspectors and armed DA investigators also are pursuing victimless misdemeanors and code violations, with sometimes tragic results. The government can define land on which residents have lived for years as “vacant” if their cabins, homes and mobile homes are on parcels where the land use hasn’t been legally established. Some have been jailed for defying the officials in downtown Los Angeles, while others have lost their savings and belongings trying to meet the county’s “final zoning enforcement orders.” Los Angeles County has left some residents, who appeared to be doing no harm, homeless.

Some top county officials insist that nothing new is unfolding. Michael Noyes, deputy in charge of code enforcement for Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley, says, “We’ve had a unit in the office through the ’70s and ’80s.” But key members of the county NAT team say that “definitely, yes,” a major focus on unincorporated areas was launched in 2006. Cooley declined to comment through his media spokesman.

Many residents insist a clearing-out is under way in these 2,200 square miles of arid land an hour north of L.A., a mountain-ringed valley at the western tip of the Mojave Desert named for elegant pronghorn herds that were all but wiped out by an 1884-94 drought. Their anxiety has prompted conspiracy theories about whether the county has its own plans for their land.

The crackdown has the strong backing of Antonovich, whose spokesman, Tony Bell, says of its critics, “I’ve probably ruined your story because you want to say it’s a horrible thing going on. … We have gotten a very, very positive response from the community.”

While Melincoff unfortunately uses the pejorative “conspiracy theory” term to describe what residents see is behind the move, it should be noted that, by the admission of the NAT itself, “a major focus on unincorporated areas was launched in 2006.” It is not a “conspiracy theory” to suggest that an admitted act is taking place nor is it a conspiracy theory to suggest that more than one individual or interest is at work behind the act taking place. While some may tend to the think the world is a place of constant accident, “coincidence theory” is simply an easy but inaccurate way to describe the social, political, and natural world. Things happen and, more often than not, they happen because something or someone made them happen.

Regardless, Melincoff continues with the story of another resident in Antelope Valley. She writes,

Oscar Castaneda, pastor of Lancaster’s historic adobe Sanctuary Seventh-day Adventist Church, built in 1934 and featured in Kill Bill, recalls the day he says he was ordered to “freeze” in front of his mobile home on isolated land where his only neighbors are rattlesnakes. Decades ago, Castaneda says the county gave him verbal approval to live there in a mobile home. He told the NAT team, which began photographing his spread: “Listen, I’ve been living over here for 22 years. And nobody has come over here to bother me.”

He says a county team member replied, “Well, we’re 22 years late.”

The article then turns to the NAT members who are responsible for the violent raids. It reads,

Tim Grover, who leads NAT as supervisor of the property rehabilitation section of L.A. County’s Building and Safety Division within the Public Works Department, says desert dwellers are not being treated overly harshly and the teams have a duty to seek out public safety, health and zoning violations.

“We don’t just storm people’s property and do things without permission,” Grover says, but, he adds, “If it’s ‘vacant’ land or ‘vacant’ property, then there’s no expectation of privacy.”

Welcome to the mind of a bureaucrat. You may not find much common sense, empathy, or compassion but you will find a mass of data and jumbled legal jargon collated to such a degree that the NSA’s supercomputers would be jealous. Indeed, combined with the ever present “rules is rules” fanaticism, the bureaucrat resembles AI more than anything naturally existing in the human habitat.

Melincoff continues,

Powerful county officials seem eager to downplay the unfolding drama in the desert. Antonovich’s communications deputy, Bell, told the Weekly: “NAT teams are used when there is toxic waste … environmental crises … potentially a parolee who has escaped. Maybe methamphetamine labs, or maybe illegal dog breeding. Very, very serious violations. … I remember one time, folks were attacked with half a dozen wild boars so big they go up to your chest.”

But that’s not the case in Antelope Valley. While Bell waxes poetic about chest high boars and meth, the reality is that peaceful people are being kicked out of their homes and off their property.

Melincoff writes,

The battle in the desert attracted national attention two weeks ago when Alan Kimbel “Kim” Fahey lost a Los Angeles Superior Court criminal case over his whimsical, soaring Phonehenge compound in the Mojave Desert, built from 108 telephone poles — but without sufficient permits. A hero to many for taking on the county, he now must work out a plan for tearing down his colorful, barn-style home; big rainbow-painted “tree house” on stilts; cabin designed to look like a railroad car; 70-foot tower of stained-glass windows; interconnecting labyrinth of bridges; and pre-existing old buildings.

Fahey, a Santa Claus look-alike with a love for Harley Davidsons and denim overalls, is still upbeat, saying of his government foes: “They are just county blobs, they don’t care about people.” Save Phonehenge West has more than 28,000 Facebook fans.

Those are not the stories told by people targeted by a system they say has morphed into a taste patrol. The desert’s fierce individualists — a racially mixed bunch including Latinos, whites and African-Americans — have banded together to resist the crackdown. A truckers’ advocacy group, the Antelope Valley Truckers Organization (AVTO), created in response to the county actions, draws an audience to its monthly meetings larger than the locally elected Littlerock Town Council, an advisory group to the county. And the Littlerock council has been upended by the locals, its members replaced with an anti-crackdown majority.

The Littlerock Town Council has proposed amendments to the Community Standards District that would take the desert dwellers, and longtime reality, into account. Bill Guild, president of the town council, says their mission is to rewrite the rules enacted by a county seat that is “almost immune to common sense.”

In 2005, Cowboy Emeterio thought he was all alone. A maintenance construction helper for the Los Angeles City Department of Water and Power, Emeterio had enjoyed a peaceful relationship with the authorities before the Nuisance Abatement Teams existed. “The guy would just tell me, ‘You know what, I need you to clean this here, I need you to put a fence around these things here in case some kids come around here and start wanting to climb over, so they don’t get hurt.”

In 2006, when Antonovich formed a NAT program in his district, Deputy District Attorney David Campbell was assigned to prosecute those who resisted the rules. “Oh man, I was one of the first motherfuckers on their docket,” Emeterio says. NAT “didn’t even have a name for themselves when they first started.” But then they “started telling me and threatening me that I had to leave. And I wouldn’t leave, so they took me to court to make me leave.”

Emeterio claims that Campbell told his public defender, “Well, he’s got ‘vacant’ land, and we want it vacant.” His voice rising, he explains the county’s view: “You’re not allowed to have anything there! Not a storage container, not a fuckin’ tire, not a nuthin’. Not a tractor. Nothing! … Well, he wanted me off the property, and I told him, ‘I’m not going anywhere, man. We’re taking this to the box.’ ”

But government, Emeterio found, is hard to beat. Although many landowners now realize they should have known this fundamental law, the requirement to obtain land-use permits for such things as living in a mobile home or storing a truck, cargo container or stack of wood was news to many. This news was delivered by NAT teams, often made up of DA investigators, Sheriff’s deputies, health inspectors, Building and Safety inspectors, zoning officers and animal control officers.

Emeterio says his wife spent a day in jail a couple years ago. The Emeterios say she was arrested for trespassing on their own land; the county NAT team says that never happens. But they were forced out of their large camper known as a fifth wheel — they had no permit for living there. Hauled into criminal court by the district attorney, Emeterio was given six months to obtain all his permits, but it took him three years. The couple were ordered to remove everything from their 5 acres, down to the piles of firewood he had long been splitting and selling.

Now he’s building a prefab home — with permits — but the couple is no longer living together due to the resulting, intense stress. He’s now homeless — “playing musical chairs,” is how he puts it — and on probation for defying the county’s cleanup orders.

About the time in 2006 that the Emeterios were targeted, Chip and Amalia Romary were pulled over in their vehicle in Palmdale. The man he thought was a traffic cop issued him a curious ticket, Chip Romary says: A citation for illegal land use. “I received a traffic ticket for illegal land use. Illegal land use. A traffic ticket.”

About the time in 2006 that the Emeterios were targeted, Chip and Amalia Romary were pulled over in their vehicle in Palmdale. The man he thought was a traffic cop issued him a curious ticket, Chip Romary says: A citation for illegal land use. “I received a traffic ticket for illegal land use. Illegal land use. A traffic ticket.”

Their story helped fuel a growing fear that the county government is tracking people using inordinate resources and invasive techniques. “I bought a piece of property, 6 and a half acres,” Romary says of the land under contention, “a wonderful piece of property. It was my life. It was everything that I wanted. It had a foundation, had water, had septic. I inherited a mobile home from my grandparents” in which he and Amalia lived.

“I showed up in court not knowing what this was all about, and they said, ‘You are illegally living on your land.’ Now, how that’s possible, I don’t know.”

Romary focuses much of his wrath on prosecutor Campbell, whom he blames for his four-day stint in jail. “My life is now a nightmare,” he says. “The courthouse is so corrupt, it’s like a mob.”

In 2006 and 2007, these and other stories began to be heard along the Sierra Highway, at parties and at the used goods and mercantile Trading Post on Pearblossom Highway in Littlerock. Tow-truck driver Richard Mesny was in trouble for storing numerous inoperable cars on his land; Lawrence Hansen, a retired electrician and former shop teacher, was under orders to remove “trash, junk and debris” that he says were his tools and construction materials.

Among those talking were the Dupuises. Jacques Dupuis had built their Llano cabin amidst the Joshua trees to code in 1984, but obtained insufficient permits and faced extensive red tape in getting his paperwork approved. An experienced builder, he recently worked as general superintendent on the “adaptive reuse” of a 17-story high-rise in downtown L.A., transforming it from offices to condos. So Dupuis figured he could get “after the fact” permits, which are granted to many who build to code in Southern California.

But codes have dramatically changed. The water well the county now required — the Dupuises use a tank supplied by a water truck — could cost $85,000 and wasn’t guaranteed to produce water. The county also aggressively acted to force them to remove a cargo container — which can be seen only by passing hawks.

The Dupuises couldn’t afford an attorney with experience in this type of criminal law, and they lost to the county on the cargo container issue. They sued the county to remove from their records the land-use violations caused by their lack of a well. But the suit was dismissed.

Reacting to multiple reports such as the Dupuises’, of being confronted by teams with guns, NAT team members who took the Weekly on the ride-along laughed and shook their heads. John Yacovone, a DA investigator, says, “We’ve heard those stories, too. It’s not the way we work. We don’t approach with our guns drawn.”

But the stories are widespread and persistent. In November 2006, Fred and Linda Kirpsie, an off-the-grid family living atop a 4,000-foot mountain, were wondering how county officials “found” their cluster of aging mobile homes and huge scrap-metal collection, at the end of four-wheel-drive-only Kirpsie Road. Did they use Google Earth? Helicopters?

Despite their extreme lifestyle, the Kirpsies had lived on “Kirpsie Mountain” for 32 years, and Fred penned “Ore Car Update,” a gold-mining column, for the Acton/Agua Dulce News. But in late 2006, when the Kirpsies returned home from a chore, their mentally disabled adult son, Paul, told them the authorities had visited.

The Kirpsies claim an armed team wearing black flak jackets pulled up in black SUVs and told Paul that his family had “no right to be here.” The NAT team returned multiple times to issue orders to remove great heaps of items from the property.

“It’s not an illegal lifestyle,” Kirpsie says. “This is our happiness.”

Criminally prosecuted, the Kirpsies agreed in March to a plea deal in which they will clear their land of every item, thus avoiding jail, says Guild of the Littlerock Town Council. They are moving to a mining town in Nevada.

But some don’t have the resources to start over. Joey Gallo, a disabled veteran on a $985 monthly pension, like the Kirpsies and Dupuises, says he also was approached by an armed NAT team. They returned several times, each time ratcheting up the citations against him, he says.

“I said, ‘Well, look, we’ve complied. We’ve taken the trash away … we picked all the weeds away. And the place looked really nice and clean.’ And they said, ‘OK, now the motor home has to go. It can’t be here. And the sheds have to go.’ ”

With the weeds removed and the trash cleared, Gallo was horrified when the county ordered him to tear down his simple, garage-like home. “It has a bedroom. It has a bathroom, it has a kitchenette, all that,” he says, close to tears.

Gallo, who is diabetic and positive for HIV and hepatitis C, has an annual income just $930 over the federal government’s poverty line, and no family to turn to. He fears the county will force him off his land soon, and he gets choked up and tearful easily. He’s distraught over what may become of his beloved dog and cat.

Interestingly, county officials appear to understand what they are forcing Gallo into: A recent NAT visit was from “a lady at the gate,” he says angrily, who handed him a flier for Stand Down, a program for homeless vets.

Until the county enforcers came calling, Gallo led a stable life. He wasn’t in any danger of becoming homeless.

These stories are a far cry from the methheads and chest high boars that Bell was storytelling about when questioned about the actual residents of the areas his office is supposedly“protecting.”

But, after going on a ride-along with the NAT team, Melincoff hits at what might be the true reason the bureaucratic terrorists are pushing these people off their own property. She writes, “But Oscar Gomez, a zoning official on a county NAT team that took the Weekly on a ride-along in June, says such violations “bring the property value down. … There are actually people that own all the property around them, even if they haven’t built there yet.”

Indeed, many residents put those pieces of the puzzle together on their own, suspecting that the real method for removing the residents was due to a push to develop the area. Some suspected a highway, others residential housing, and others suspected the entire move was about control. All of those suspicions are most likely correct, even if they were labeled “conspiracy theories” at the time.

After reading Melincoff’s article (which I highly suggest accessing and reading in full) and watching the residents’ testimony on camera, one can’t help but be reminded of Woody Guthrie’s famous line “As through this life I’ve traveled /I’ve seen lots of funny men/some will rob you with a six gun/and some with a fountain pen/but as through this life you ramble/as through this life you roam/you will never see an outlaw/drive a family from their home.”

After reading Melincoff’s article (which I highly suggest accessing and reading in full) and watching the residents’ testimony on camera, one can’t help but be reminded of Woody Guthrie’s famous line “As through this life I’ve traveled /I’ve seen lots of funny men/some will rob you with a six gun/and some with a fountain pen/but as through this life you ramble/as through this life you roam/you will never see an outlaw/drive a family from their home.”

Given the history of California, however, I’m also inclined to remember another famous Guthrie line: “California is a garden of Eden/a paradise to live in or to see/but believe it or not you won’t find it so hot/if you ain’t got the Do Re Mi.”